GIOS Lecture Notes - Part 3 Lesson 2 - Memory Management

Memory Management

Goals

- Manage physical memory on behalf of one or more executing processes

- In order to not impose unnecessary limits on these processes we decouple virtual and physical memory

- Basically everything uses virtual addresses, which are then translated to physical addresses

- To be able to do this successfully the OS must be able to:

- Allocate physical memory

- Needs data structures and algorithms to track usage, replacement, and free memory

- Needs mechanisms to replace contents of physical memory with contents on temporary storage, such as a disk, and swap out unused memory contents for it

- Arbitrate how physical memory is accessed

- OS must be able to interpret and verify a process’ memory access

- This requires being able to quickly translate a virtual address into a physical address

- leverage hardware support and clever DS design

- Virtual address space is subdivided into pages

- physical divided into page frames of the same size

- Allocation then is about mapping pages to page frames

- Arbitration is done using page tables

- Pages aren’t the only option, segment-based memory management uses segments

- Allocate – segments

- Arbitrate – segment registers

- Paging is more common in most OS’s

Hardware Support

- in order to make allocation and arbitration efficient, hardware mechanisms help out

- MMU - memory management unit

- transates virtual to physical addresses

- reports faults for things like illegal accesses or inadequate permissions, or page isn’t present in memory (page fault!)

- Dedicated Registers for use during address translation

- page-based system: pointers directly to page table

- segment-based system: base address and limit size of segments, number of segments

- Cache-Translation Lookaside Buffer

- valid VA-PA translations: TLB

- avoid needing to look up or re-derive translations regularly, cache them for faster access

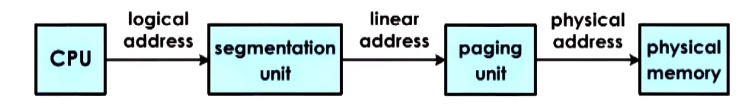

- Translation

- actual PA generation done in hardware. the OS maintains certain data structures for necessary information for translation, but actual translation is done by hardware.

- This means that hardware dictates what memory management systems are supported. Pages vs Segments, which dedicated registers are available, size of TLB all drive memory management approach, and are all determined by hardware and not the OS.

- Some things, like allocation and replacement algorithms, are done by the OS in software.

Page Tables

- For each virtual address, a page table entry exists that determines the actual physical location that corresponds to it

- Virtual memory pages and physical memory page frames are the same size

- Because of this size matching we don’t have to keep track of every virtual address in a page. We only have to track the first virtual address in a page, and then map that to the first physical address in the page frame. From there, offsets will match correctly.

- This substantially saves space on the page table

- The language to describe this is the Virtual Page Number (VPN) and the offset

- The corresponding physical memory are Physical Frame Number (PFN) and the offset

- Physical memory for full address mapping when paging in is allocated on first touch.

- Unused pages are reclaimed from physical memory

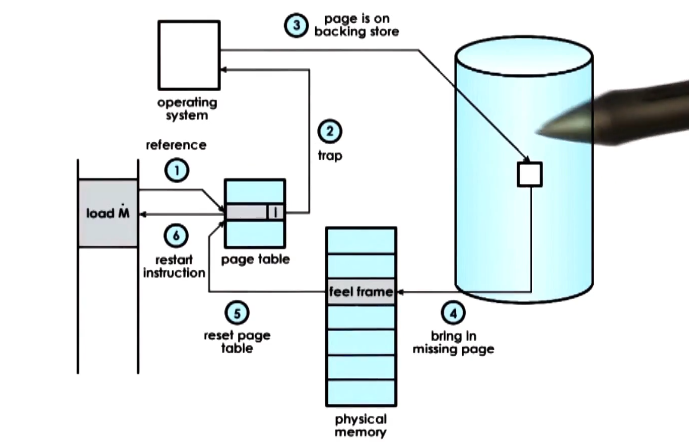

- Page tables track additional information in storage bits

- Valid bit indicates whether the page frame is actually in memory

- If hardware finds that a mapping is invalid, it will raise a fault and trap to the operating system

- OS gets to decide:

- if access is permitted

- where is page located

- where should it be brought into DRAM

- reestablish the mapping on reaccess

- Page tables are per-process

- on context switch, switch to valid page table

- update relevant registers, e.g. CR3 on x86 that points to base of page table

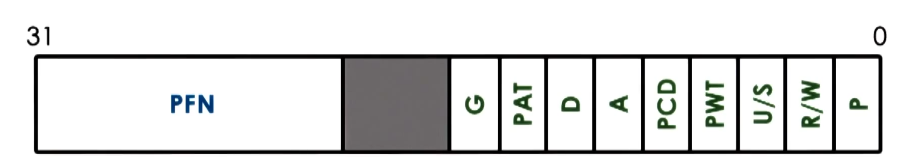

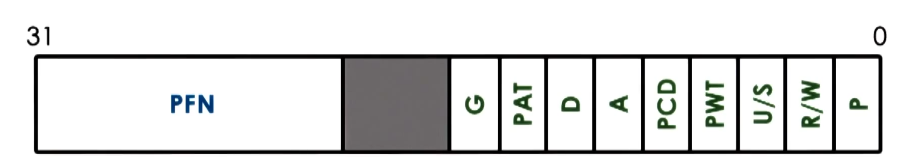

Page Table Entry

- Every entry will have a PFN and a valid bit, at minimum

- valid bit also called present bit

- There are several other fields that may be present depending on OS and hardware

- Dirty bit

- gets set whenever a page is written to

- useful for filesystems where files are cached in memory, as it will tell the OS which files have been written to and so need to have changes pushed back out to disk

- Accessed (for read or write)

- protection bits => RWX

- useful for WorX for example

- X86 Page Table Entry Example

- Present

- Dirty

- Accessed

- R/W => permission bit: 0->R, 1->R/W

- 0 indicates read-only, 1 indicates read/write allowed

- U/S => permission bit: 0->usermode, 1-> supervisor mode only

- Others: caching related info (write through, caching disabled, etc)

- Unused: for future use

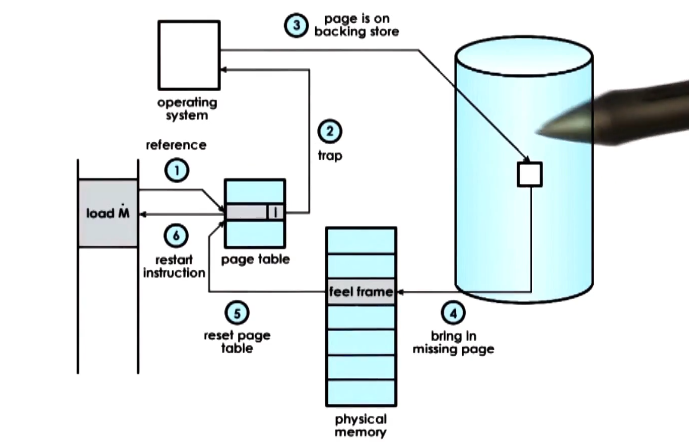

Page Fault

- The MMU relies on page table entries to both perform address translation and to establish validity of each access

- If the hardware determines that an acess cannot be performed it causes a page fault

- The CPU will place an error code on the stack of the kernel, and then generate a trap into the kernel

- The kernel will then generate a page fault handler which will determine the action that must be taken based on the error code and the address that caused the fault

- bring page from disk to memory

- permission protection error – SIGSEGGV (segfault!)

- on x86 the error code information is generated from some of the flags in the page table entry and the faulting address is stored in a register cr2

Page Table Size

- To calculate the size of a page table we know that a page table has # of entries equal to number of virtual pages in a virtual address space

- We also know the information it must hold for each entry

- on a 32-bit architecture:

- PTE => 4 bytes, including PFN + flags

- VPN => 2^32 / page size

- with a common 4kb page size:

- calculated as: (2^32/2^12)*4b = 4MB – PER PROCESS

- when converting to 64-bit (just change 32 to 64 in equation) this comes out at 32PB per process. Obviously unworkable.

- To solve this, remember:

- process doesn’t use the entire address space

- even on 32-bit architecture doesn’t use all of 4MB

- but page table assumes an entry per VPN, regardless of whether corresponding virtual memory is needed or not

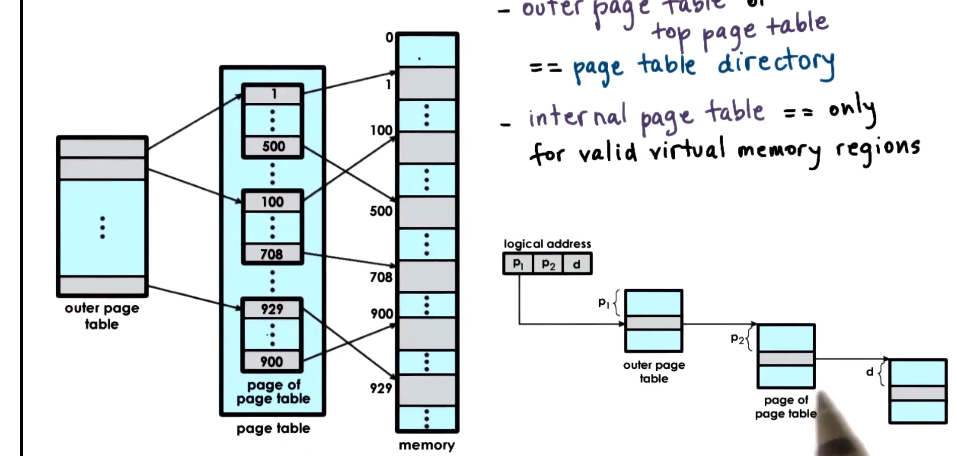

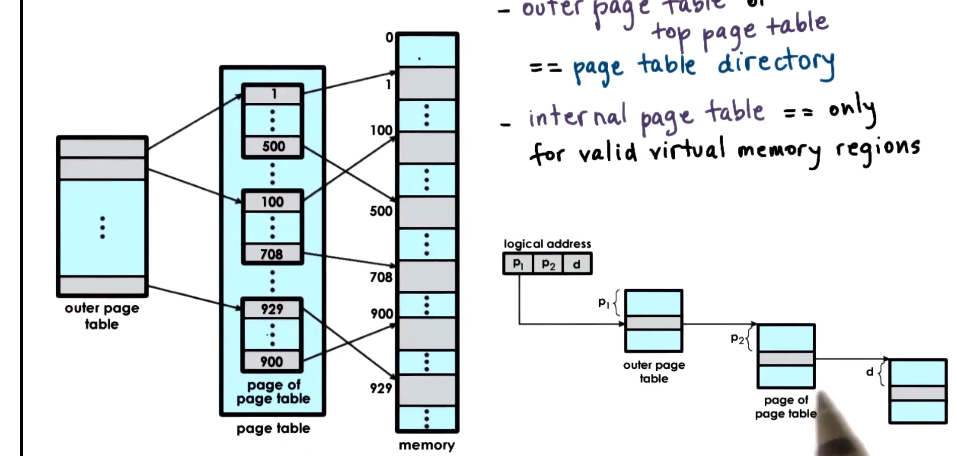

Hierarchical Page Tables

- Solution to the space issue is that page tables aren’t really flat anymore

- Outer page table or Top page table == page table directory

- elements are not pointers to pages, but to internal page tables

- Internal page tables

- only for valid virtual memory regions - save some space on not showing unused virtual memory

- On malloc a new internal page table may be allocated

- To find the right element in a multilevel structure the virtual address is split

- This format uses:

- 10 bits for outer page table index (p1)

- 10 bits for the internal page table index (P2)

- 10 bits for page offset to physical memory (d)

- This allows storage of addresses such that: 2^10 * page size == 1mb

- don’t need an inner table for each 1mb virtual memory gap, also saving size

- This style can be extended using additional layers

- page table directory pointer (3rd level)

- page table directory pointer map (4th level)

- This is particularly important on 64bit architectures

- they are much larger and much more sparse

- the ability to exclude gaps saves more in a sparse environment, so very useful here

- This has tradeoffs, of course

- pros:

- smaller internal page tables/directories

- granularity of coverage, excluding gaps

- potential reduced page table size

- cons:

- more memory accesses required for translation

- increased translation latency

Speeding up Translation Lookaside Buffer (TLB)

- As covered above, adding levels to the page table structure will reduce size, but add latency to memory accesses

- Single-level page table

- 1x access to page table entry

- 1x access to memory

- Four-level page table

- 4x access to page table entries

- 1x access to memory

- obviously slower

- Page Table Cache is the standard technique to deal with this latency

- In most architectures, there is a haradware cache for storing address translaations. This is the TLB.

- If there is a TLB hit, we can skip going all the way down to memory

- On a TLB miss, we perform address translation steps as normal

- The TLB has validity and protection bits, similar to PTEs, for the same reasons

- Even a small number of cached addresses result in a very high TLB hit rate. This is because there is usually a high temporal and spatial locality for memory references

- On x86 Core i7:

- per core:

- 64-entry data TLB

- 128-entry instruction TLB

- 512-entry shared second-level TLB

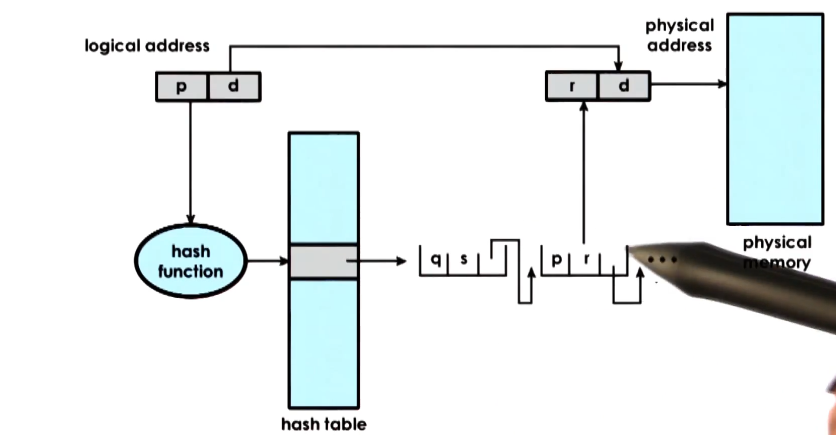

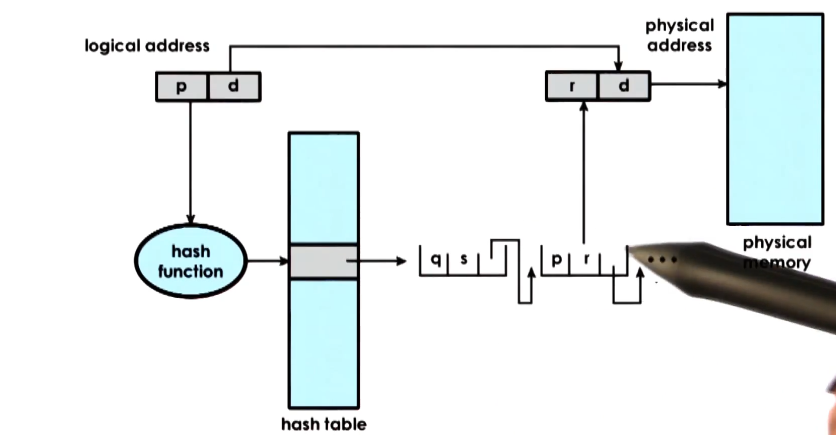

Inverted Page Tables

- Different architecture entirely from multi-level page tables above!

- Physical memory is much smaller than virtual memory. Inverted page tables try to address that

- To find the translation, the page table is searched based on the process ID and the first part of the physical address

- The problem with these is that it requires linear search of page table to find matching pid/p

- because memory can be assigned arbitrarily, the page table is not ordered in a useful way

- In practice the TLB catches a lot of this, minimizing the impact

- However, misses are still painful enough that they must be addressed

- To address this, inverted page tables are supplemented with hashing tables

- A hash is computed on a part of the address, and that is an entry in the hash table

- points to a linked list of possible matches for part of the address

- speeds up process of linear search by narrowing down to a few possible hash matches. Thus, this speeds up overall address translation

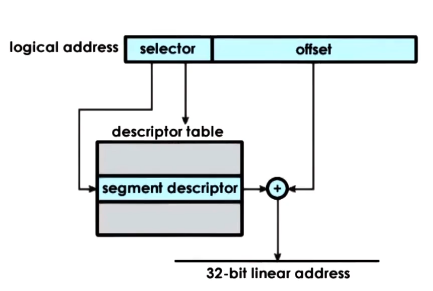

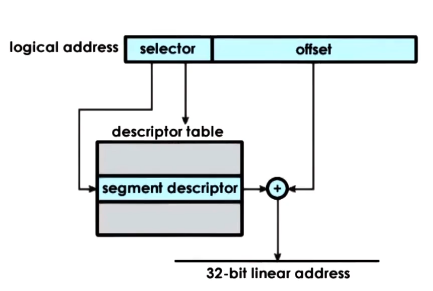

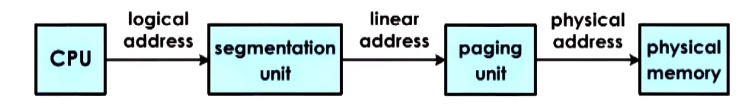

Segmentation

- segments == arbitrary granularity, arbitrary size

- should correspond to some logical components of the address space, such as code, heap, data, stack, etc

- address consistes of a segment descriptor and and offset

- descriptor is used with a descriptor table to determine info regarding physical address. combined with offset to get to the actual physical address

- In its pure form, a segment represents contigous physical memory

- in this case segment would be defined by its base address and limit registers

- In practice, often used in combination with paging

- The type of address translation that’s possible on a given platform is determined by the hardware

- IA x86_32 => segmentation + paging

- linux: up to 8k segments available per process, plus another 8k global segments

- IA x86_64 => paging

- segmentation + paging supported for backward compatibility, but default mode is to just use paging

Page Size Redux

- In prior examples, we used 10bit or 12bit offsets. Offset determines total number of addresses per page and therefore page size

- In practice, systems support different page sizes

- 4kb is default in Linux x86 env

- Other common sizes:

- Large Pages == 2mb page size and 21 bits offset

- Reduces page table size 512x compared to 4kb pages

- Huge Pages == 1gb page size and 30 bits offset

- Reduces page table size 1024x compared to 4kb pages

- Larger pages pros

- fewer page table entries

- smaller page tables

- more TLB hits

- Larger pages cons

- internal fragmentation => wastes memory

Memory Allocation

- Memory allocator

- determines VA to PA mapping

- address translation, page tables, etc s,imply determine PA from VA and check validity/permissions

- kernel-level allocators responsible for:

- allocating memory regions for the kernel,

- static process state (code/stack/data etc)

- keeping track of the free memory in the system

- user-level allocators responsible for:

- dynamic process state (heap, malloc/free)

- once the kernel allocates memory to a malloc call, kernel is no longer responsilbe for management of that space

- instead it will be managed by whatever user-level allocator is used, e.g. dlmalloc, jemalloc, hoard, tcmalloc

Memory Allocation Challenges

- Key challenge of naive implementation of memory allocation is fragmentation. Contiguous stretches of free memory may be substantially smaller than overall free memory depending on circumstances of memory allocations and releases

- Called “external fragmentation”

- One solution is for allocator algorithm to attempt to aggregate free areas. Hypothetical explanation given in lecture

Allocators in the Linux Kernel

- Relies on 2 basic allocation mechanisms

- Buddy Allocator

- starts with 2^x area

- on request, subdivide 2^x chunks until it finds smallest 2^x chunk that can satisfy request

- e.g. start with 64. given a request for an 8 page chunk, subdivide 64 into 32, then one 32 into 16, then one 16 into an 8.

- left afterwards would be a 32, a 16, and two 8s (one of which is not free)

- On free, recombine adjacent chunks back into larger size if possible (this is the source of the ‘buddy’ name, as it combines ‘buddy’ chunks)

- note – the reson for one using powers of 2 is that this means the addresses of buddy chunks will differ only by 1 bit. this makes it easier to perform checks when combining or splitting chunks

- pros

- aggregation works well and fast

- cons

- 2^x granularity means there will be some internal fragmentation, because there are many data structures that are not close in size to a power of 2. this is addressed by the slab allocator.

- Slab Allocator

- builds custom object caches on top of slabs

- caches for common object types/sizes, on top of contiguously allocated physical memory

- when the kernel starts it will pre-create caches for the different object types

- when an allocation comes, it will go straight to cache, and use one of those elements

- if there is a cache miss, the kernel will create a new slab and will allocate additional portion of memory to be managed by slab allocator

- pros

- avoids internal fragmentation

- external fragmentation not an issue, as memoy allocation sizes are custom-fit to the objects that will make use of them anyway

Demand Paging

- Because virtual memory is much larger than physical memory, allocated pages of virtual memory are not always present in physical memory.

- instead, backing physical page frame saved and restored to/from secondary storage

- this is referred to as demand paging

- pages swapped in/out of memory and a swap partition (e.g. on disk)

- note that after page swapping the new PA will likely be different from the original PA.

- A page can be “pinned”, disabling swapping on it

Page Replacement

- When should pages be swapped out?

- periodically, when the amount of occupied memory exceeds a threshold

- when memory usage is above threshold (high watermark)

- when CPU usage is below threshold (low watermark)

- Which pages should e swapped out?

- pages that won’t be used in the future. the challenge is, of course, how to know which pages those are.

- history-based prediction => least-recently used (LRU policy)

- access bit on PTE to track if page is referenced

- pages that don’t need to be written out to disk

- writes to disk are slow, so avoid if possible

- dirty bit on PTE to track if modified

- avoid non-swappable pages (pinned)

- In Linux (and in many other OS’s)

- there are parameters available to configure the page replacement function of the system

- parameters to tune thresholds: target page count

- categorizes pages into different types

- e.g. claimable, swappable

- default page swap algorithm is “second chance” varation of LRU

- performs two scans of a set of pages before making swap determinations

Copy on Write (COW)

- Systems rely on memory module hardware (MMU) to perform translation, track access, and enforce protection

- However, it is also useful to build other services and optimizations

- On process creation

- copy entire parent address space

- However, many pages are static, and don’t change

- so why keep multiple copies?

- Instead, on creation

- map new VA to original physical page

- write protect original physical page

- if only read

- save memory and time to copy

- on write

- page fault and copy

- this allows the OS to pay the copy cost only if necessary

Failure Management Checkpointing

- Checkpointing == failure & recovery management technique

- periodically save entire process state

- failure may be unavoidable, but can restart from checkpoint, so recovery will be much faster

- simple approach

- pause and copy entire process state periodically

- very expensive, and unnecessary

- better approach

- take advantage of MMU

- write-protect and copy everything once

- then copy only diffs of dirtied pages for incremental checkpoints

- Recovery process will be more complex: rebuild from multiple diffs, or in background

- The same basic processes used in checkpointing can also be used in other services

- Debugging

- rewind-replay

- rewind == restart from checkpoint

- gradually go back to older checkpoints until error is found

- Migration

- capture checkpoints, transfer to another machine

- continue on another machine

- useful for disaster recovery or consolidation in data centers

- repeated checkpoints in a fast loop until pause and copy becomes acceptable/unavoidable