GIOS Lecture Notes - Part 3 Lesson 4 - Synchronization Constructs

Synchronization Constructs

Limitation of mutexes and condition variables

- error prone / correctness / ease of use

- unlock wrong mutex, signal wrong condition variable, etc

- lack of expressive power

- needed helper variables for access or priority control

- low level support

- hardware atomic instructions

Spinlocks

- basic sync construct

- like a mutex

- mutual exclusion

- lock and unlock (free)

- block a critical section

- BUT

- when the lock is busy the suspended thread isn’t blocked, but instead is spinning.

- running on cpu and repeatedly checking lock to see if it’s free

- burn CPU cycles until lock is free or thread is preempted

- when the lock is busy the suspended thread isn’t blocked, but instead is spinning.

- like a mutex

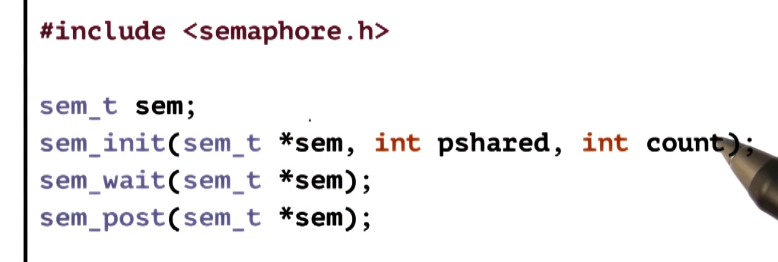

Semaphores

- common sync construct in OS kernels

- like a traffic light: STOP and GO

- similar to a mutex but more generalizable

- Represented by an integer value

- on init

- assigned a max value (positive int)

- on try (wait)

- if non-zero -> decrement and proceed

- if zero, block and wait

- number of threads allowed to proceed is the maximum value (counting semaphore)

- allow us to express count related synchronization

- if initalized with 1, it is roughly equivalent to a mutex

- on exit (post)

- increment

POSIX Semaphore API

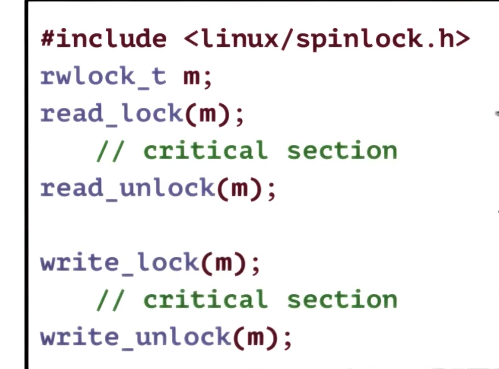

Reader Writer Locks

- Syncing different types of access

- read (never modify)

- shared access

- write (always modify)

- exclusive access

- RWlocks specify the type of access, then locks behave accordingly

- read (never modify)

- rwlock support in Windows, Java, POSIX

- read/write == shared/exclusive

- Semantic differences:

- recursive read.lock -> differs between implementations on what happens on read.unlock

- in some cases it may unlock every single recursively locked rwlock

- in others, a separate read.unlock is required for each

- upgrade/downgrade priority?

- in some cases a reader may be given priority to upgrade the lock to write access, compared to newly arriving requests for a write lock.

- interaction with scheduling policy

- e.g. may block a reader if higher priority write waiting

- recursive read.lock -> differs between implementations on what happens on read.unlock

Monitors

- One problem with constructs so far is that they require devs to pay attention to the pairwise operations lock/unlock wait/post etc

- Monitors specify

- what is the shared resource being protected by the sync construct

- what are all possible entry procedures to the resource

- explicitly specify any relevant condition variables

- On entry

- lock, check, etc all handled when thread is entering the monitor

- On exit

- unlock, check, signal all handled when thread is exiting the monitor

- Monitors are higher level construct

- included in MESA by XEROX PARC

- Java

- synchronized methods generate monitor code

- when compiled the resulting code will include all appropriate locking and checking. only notify() must be done explicitly

- Monitoring also refers to the programming style that uses mutexes and condvars to describe entry and exit codes from critical section (as described in unorthodox example in enter/exit critical section material from earlier lecture)

More Synchronization Construct

- Serializers

- make it easier to define priorities

- hide the need for explicit signaling and use of condvars

- Path expressions

- requires the programmer specify the regex that captures the correct sync behavior

- instead of locks or other such, programmer would specifiy e.g. “many reads OR single write” and runtime will enforce this

- Barriers

- inverse of semaphore

- blocks all threads until N threads arrive at the given point in execution

- Rendezvous points

- also a sync construct that waits for multiple threads to meet that particular point in execution

- Optimistic wait-free sync (RCU)

- efforts to achieve concurrency without explicitly locking and waiting

- bet on the fact that there won’t be any conflict due to concurrent writes and it’s safe to allow reads to proceed concurrently

- Read Copy Update lock that’s part of Linux kernel is a good example

- All above methods need hardware support to atomically make updates to a memory location

- this will now be discussed in detail

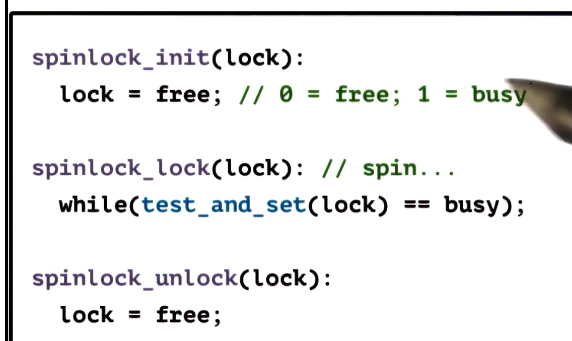

Sync Building Block: Spinlock

- basic sync construct, used in creating more complex constructs

- Using Anderson paper to explore them further

- Alternative implementations of spinlocks

- techniques generalize to other situations (e.g. atomics)

- spinlock requires hardware support

- to ensure that checking of lock value and setting of lock value happen atomically

- problem is that check + update takes multiple cycles, and concurrent check/update on different CPUs can overlap

- hardware-supported atomic instructions!

Atomic Instructions

- Hardware-spedific

- not all hardware supports the same list

- stuck specializing/optimizing to available atomics

- different atomics may peform better/worse on different architectures

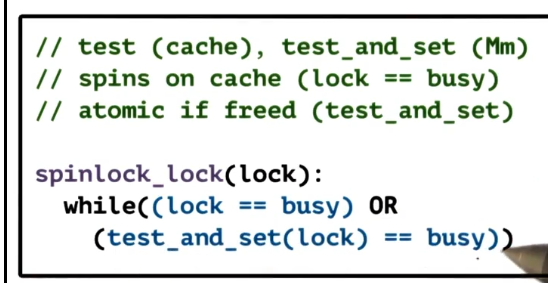

- test_and_set

- automatically returns (tests) original value and sets new value = 1 (busy)

- with multiple threads contending for this operation

- first thread: test_and_set(lock)=>0: free

- subsequent threads: test_and_set(lock)=>1: busy

- they will reset lock to 1(busy) but that’s ok

- read_and_increment

- compare_and_swap

- not all hardware supports the same list

- Guarantees

- atomicity

- mutual exclusion

- queue all concurrent instructions but one

- atomic instructions == critical section with hardware-supported synchronization

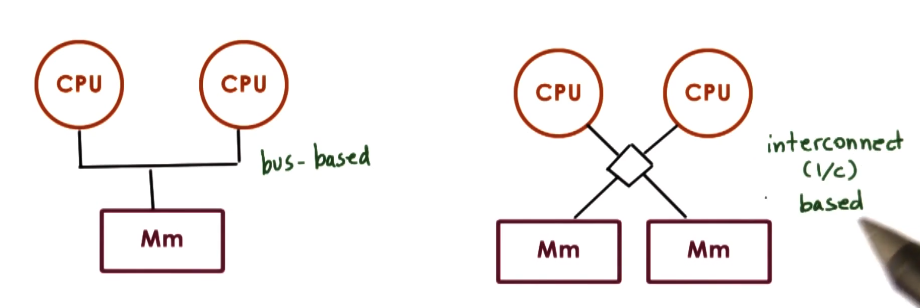

Shared Memory and Multiprocessors

- Called shared memory multiprocessors because the memory is available to all CPUs

- aka symmetric multiprocessor, or SMP

- Caches

- hide memory latency

- SMP memory further away due to contention between CPUs for the shared memory

- when a write to memory is tried, several things can happen

- no – cache writing may not be allowed, and instead the write is to the memory module itself

- write-through – write to both cache and memory

- write-back – in some architectures, write can be applied in cache but actual update to memory applied later

- Cache Coherence

- how do we handle data showing up in multiple caches / memory modules

- In some architectures this must be dealt with in software

- non-cache-coherent (NCC) architectures

- Sometimes hardware has it covered, though, will align values across caches

- cache-coherent (CC) architectures

- two main approaches for handling cache coherence

- write-invalidate

- if one cpu changes value of X, hardware makes sure all other caches references to X are invalidated and will result in a cache miss and will be pushed to memory

- pros

- lower bandwidith on shared interconnect

- amortize the cost of coherence traffic. after first one causes invalidation no further handling is needed

- write-update

- if one cpu changes value of X, hardware updates all other references to X in other caches

- pros

- updated data available immediately

- which one is used is determined by hardware, you don’t get a choice as the dev

- write-invalidate

- Cache Coherence and Atomics

- atomics always issued to the memory controller.

- this allows central entry point where everything can be ordered and synchronized

- however, imposes severe performance penalties

- also, generates coherence traffic to update/invalidate all cached copies of a memory reference, even if no changes were made to value, to guarantee correctness

- Atomics on SMP systems are expensive!

- expensive because of bus or I/C contention

- expensive because of cache bypass and coherence traffic

Spinlock Performance Metrics

- What are our objectives?

- Reduce latency

- defined as time to acquire a free lock

- ideally we want to immediately execute an atomic

- Reduce waiting time (delay)

- defined as time to stop spinning and acquire a lock that has been freed

- again, ideally immediately

- Reduce contention

- defined by traffic on bus or network IC

- again, ideally zero extra traffic generated

- Reduce latency

Test-and-Set Spinlock

- Pros

- most systems support this, very portable

- minimal latency

- potentially minimal delay (spinning continuously on the atomic)

- Cons

- causes a ton of contention - processors go to memory on each spin

- this is because it continously spins on the atomic instruction, which as discussed above must always be checked in memory

- let’s see how to fix this

- Instead of testing lock itself, we could test cached copy. if it’s free, only then would we execute the atomic and go to memory

- sometimes called “spin on read” or “spin on cached value”

- slightly worse on latency and delay, but still good.

- for contention it’s better, but….

- NCC architectures there’s literally no difference

- CC-WU it’s ok, but when lock is freed all CPUs looking at it will see it at once, and all will execute the atomic, going to memory and spiking traffic

- CC-WI – very bad. Same problem as WU, but every single attempt to acquire the lock will not only generate contention, but will also generate invalidation traffic.

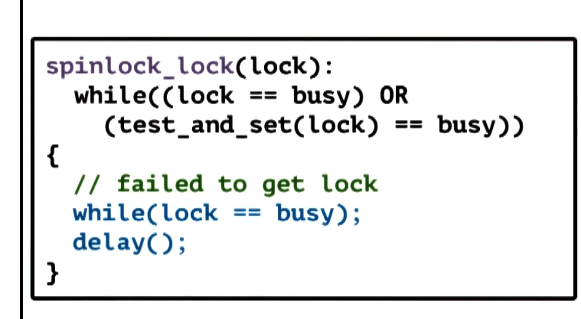

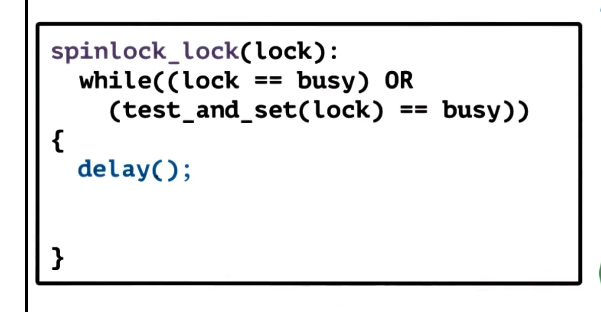

Spinlock “Delay” Alternatives

- delay after lock release

- all CPUs see lock is free

- not all attempt to acquire it

- Pros

- contention improved

- Latency is ok, still need a memory reference initially and atomic instruction

- Cons

- Delay is much worse, as we are forcing additional delay explicitly

- Delay after each lock reference

- doesn’t spin constantly

- works on NCC architectures

- but can hurt delay even more

- How do we pick a correct “delay” to use for these alternatives?

- Static Delay

- based on fixed value, e.g. CPU ID

- pros - very simple approach

- cons - unnecessarily long delay under low contention (and presuambly too low under high contention if set wrong?)

- Dynamic Delay

- much more popular

- backoff-based

- random delay in a range that increases with percieved contention

- sounds similar to CN content on network flow control algorithms

- perceived == failed test_and_set() operations

- delay after each reference will keep growing based on contention OR length of critical section. noisy signal

- Static Delay

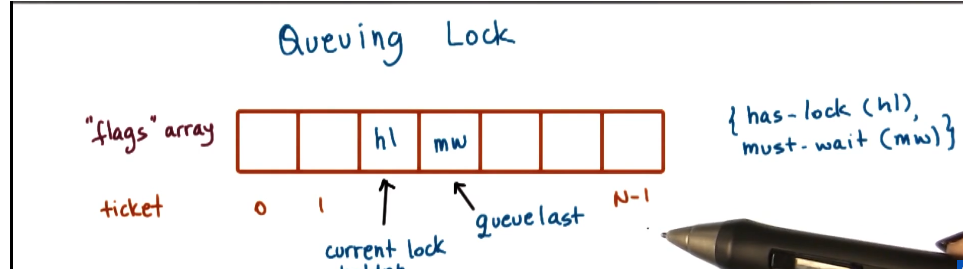

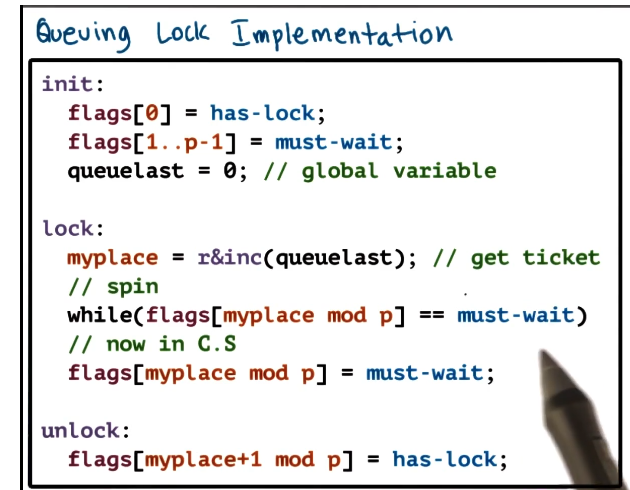

Queuing Lock

- Common problems in spinlock implementations:

- everyone tries to acquire a lock at the same time once lock is freed

- solution: delay alternatives

- everyone sees the lock is free at the same time

- solution: anderson’s queueing lock!

- everyone tries to acquire a lock at the same time once lock is freed

- array of flags with up to n elements (where n is number of processors in system)

- every flag has one of two values

- has-lock (hl)

- must-wait (mw)

- every flag has two pointers

- to the current lock holder

- the last element in the queue

- every flag has one of two values

- when a new thread arrives at the lock it recieves a unique ticket, that is the current position of the thread in the lock

- queue-last value is incremented

- thread is assigned the next position in the queue

- the read and increment of the queue-last pointer must be atomic

- assigned queue[ticket] is a private lock

- enter critical section when you have lock

- queue[ticket] == must_wait => spin

- queue[ticket] == has_lock => enter critical section

- signal/set next lock holder on exit

- queue[ticket+1] == has_lock

- Donwsides

- assumes read_and_increment atomic is available in the system

- O(N) size

- All of the spinning happens on assorted other variables, the atomic is only used to give out tickets to new threads on arrival.

- Latency

- read and increment operation takes more cycles. latency not great

- delay is very good – directly signal next cpu/thread to run, no broadcasting

- contention is much better than alternatives – no spinning on atomics. but requires cc architecture and cache line aligned elements

- only 1 cpu/thread sees the lock is free and tries to acquire lock!

Paper Review

Morsel “30. Spinlock Performance Comparisons” covers findings paper deeply, and explains why each of the approaches above does better or wose in different loads and architectures.

Go through and review this in depth for exam. [Update notes here]. This is definitely exam question fodder