GIOS Lecture Notes - Part 3 Lesson 5 - I/O Management

I/O Management

- Focus on the mechanisms that OS’s use to represent and manage I/O hardware devices

- Notably block devices and file systems

I/O Devices

- Key features of a device

- control registers

- command - CPU uses to control what the device does

- data transfers - used for the CPU to control data transfers in and out of device

- status - used by the CPU to find out what’s happening on the device

- microcontroller

- on-device memory

- other logic

- e.g. analog to digital converters

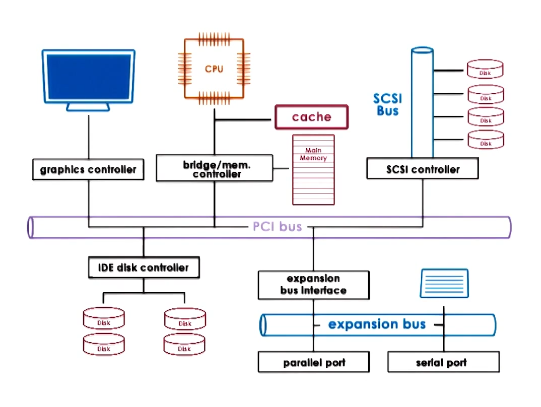

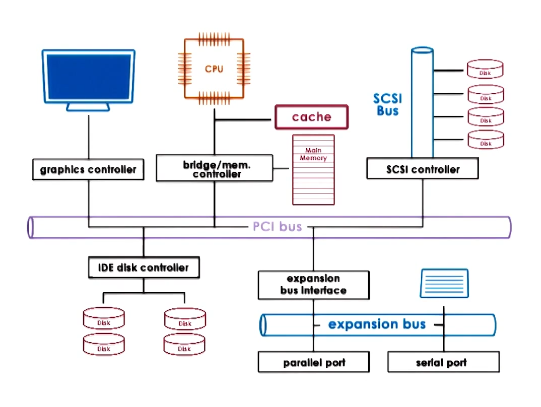

CPU - Device Interconnect

- Devices interface with the rest of the system via a controller that’s integrated as part of the device packaging

- Peripheral Component Interconnect (PCI)

- Common architecture is PCI Express (PCIe)

- (more advanced than original PCI or PCI-X bus)

- Usually includes PCI eXtended (PCI-X) for backwards compatibility

- Other types of interconnects

- SCSI Bus

- Peripheral Bus

- Controllers determine what kinds of interconnects a device can use

- Bridges handle differences between different types of interconnects

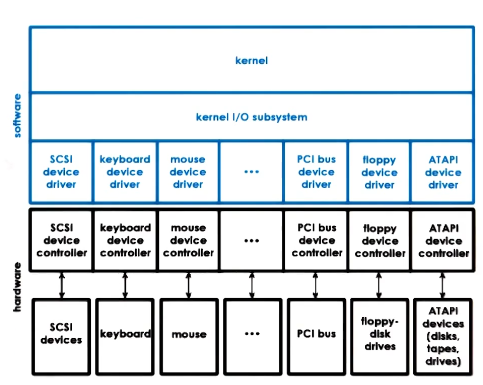

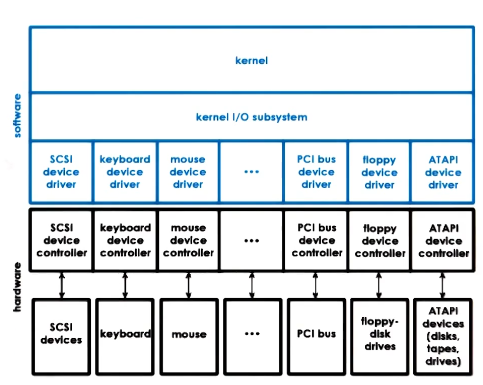

Device Drivers

- OS’s support devices via device drivers

- Device Drivers

- per each device type

- Responsible for device access, management, and control

- includes how instructions can be passed from higher level systems like the kernel or applications to the actual device

- includes how the system should respond to device-level events like errors or notifications

- provided by device manufacturers per OS/version

- each OS standardizes interfaces to device drivers

- so that the manufacturers can stay within a framework

- this achieves device independence – the OS does not need to be specialized for any given device

- this achieves device diversity – any device manufacturer can write a driver for any given OS knowing there’s a standardized interface

Types of Devices

- To deal with such device diversity, devices are usually grouped into types

- Block: Disk

- read/write blocks of data

- direct access to arbitrary block

- Character: Keyboard

- get/put characters

- serial sequence of characters

- Network Devices

- kind of a special case, somewhere between block and character. stream of data chunks, sometimes of different sizes

- OS representation of a device == special device file

- allows any other existing OS file mechanisms to interact with devices

- Unix-like systems

- all devices appear as files under /dev directory

- handled by special filesystem, not the normal one

CPU-Device Interactions

- The main way PCI makes devices available to the CPU is to represent these devices’ registers in a way similar to how the CPU accesses memory

- Device registers appear to the CPU as memory locations at a specific physical address

- Memory-mapped I/O

- part of ‘host’ physical memory is dedicated for device interactions

- Base Address Registers (BAR) – control this dedicated memory

- Configured during boot process and determined by PCI configuration protocol

- I/O port model

- dedicated in/out CPU instructions for device access

- target device (I/O) port and value in register

Path from Device to CPU

- The path from the device to the CPU can take 2 routes

- Interrupt

- devices can generate interrupts to CPU

- Pros

- can be generated as soon as possible

- Cons

- interrupt handling steps generate overhead in several ways

- Polling

- CPU can poll devices by reading their status registers

- Pros

- can be done when convenient for OS

- Cons

- either delay or additional CPU overhead depending on implementation

- Choosing between them will depend on a variety of charteristics

- type of device

- interrupt complexity

- overall load on the system

Device Access – PIO

- Programmed I/O == PIO

- Requires no additional hardware support

- CPU issues instructions by writing into the command registers of the device

- CPU controls data movement by accessing data registers of the device

- Example: NIC, data == network packet

- write command to request packet transmission

- copy packet to data registers

- repeat until packet sent

- e.g. 1500b packet; 8byte regs or bus

- 1 (for bus command) + ~188 for data => ~189 CPU store instructions

Direct Memory Access (DMA)

- Alternative to PIO

- Relies on special hardware support – DMA controller

- CPU “programs” the device

- via command registers

- via DMA controls

- Example: NIC

- write command to request packet transmission

- configure DMA controller with in-memory address and size of packet buffer

- e.g. 1500B w/ 8 byte regs or bus => 1 store instruction + 1 DMA configure

- less steps, but DMA config is more complex

- therefore, for smaller transfer PIO is better than DMA, as DMA configuration takes many cycles

- For DMAs:

- data buffer must be in physical memory until transfer completes

- cannot swap it out to disk, as DMA controller can only interact with physical memory

- this is done with pinning regions (non-swappable pages)

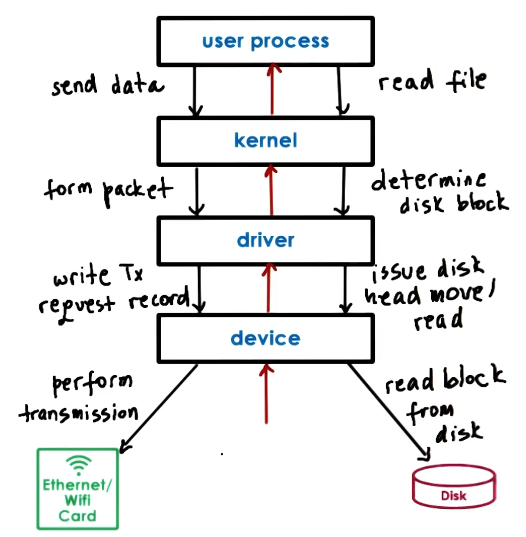

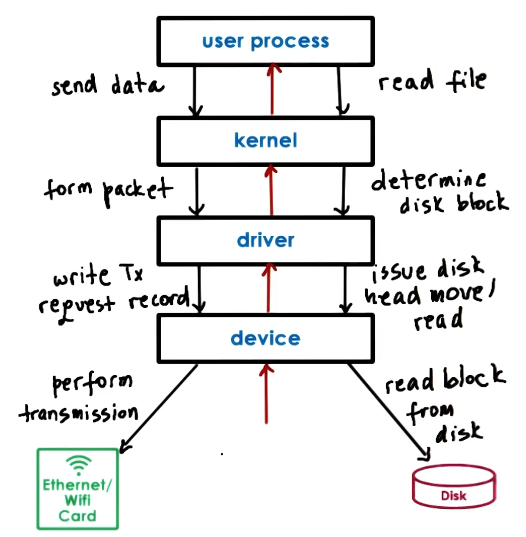

Typical Device Access

- Typical ways a user process interacts with a device:

- system call to kernel

- in-kernel stack for target device

- device request configuration

- driver knows all the specific device things, it will handle minutae

- Device performs request

- call chain is then traversed in a reverse manner back up to user process

OS Bypass

- It is not actually necessary to go through the kernel to get to a device

- Some devices can be configured to be directly access from User Level

- This is called OS Bypass

- OS Bypass

- device registers and/or data directly accessible

- OS does the configuration then gets out of the way

- Jump straight from user process to device driver

- requires a user-level driver library for user process to talk to device driver. equivalent to kernel device drivers

- OS retains coarse-grain control, such as enable/disable or add/remove permission

- relies on device features

- device must have sufficient registers so that OS can map some registers to user process but still retain access to whatever registers that are used for configuration and control

- must also be able to share the device across multiple user processes

- demux capability

- one device wants to send data back to one of multiple user processes, the device must be able to figure out how to correctly send desired data to target process’ address space

- this means the device must be able to look inside data to understand where it should go

- In normal device usage path, kernel would normally handle all of this, putting less burden on the device and libraries

- ioctl() command on Linux

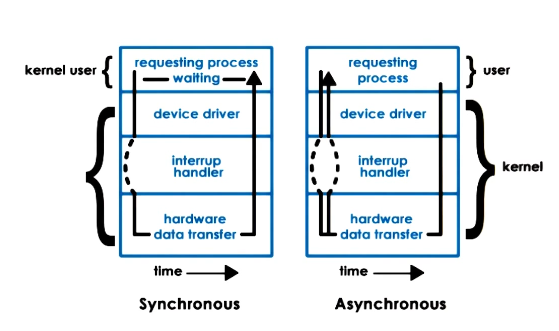

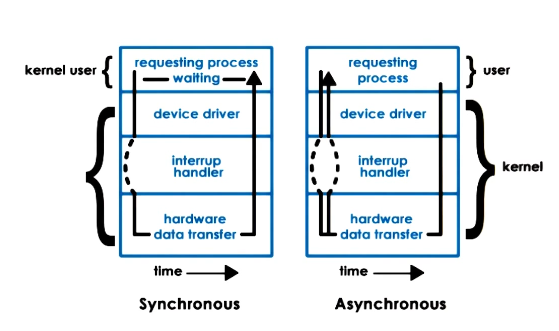

Sync vs Async Access

- When an I/O request is made, usually the user process needs a response from the device, even just an acknowledgement

- What happens to the user process while waiting on that response?

- Synchronous

- user process blocks, placed on wait queue

- Asynchronous

- process continues

- later:

- process checks and retrieves result

- OR process is notified that the operation completed and the results are ready

- similar to interrupt vs polling tradeoffs

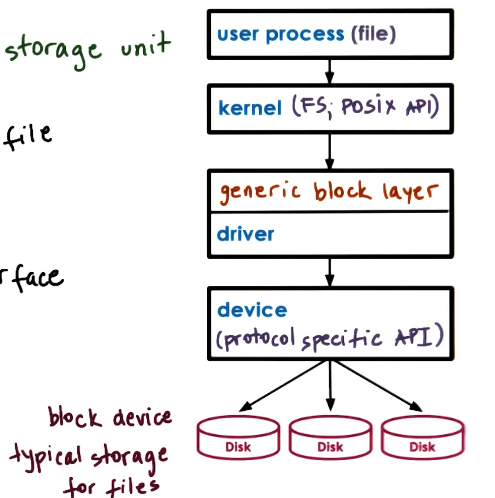

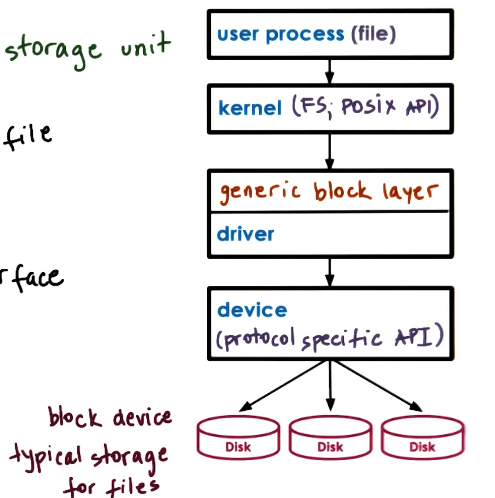

Block Device Stack

- Block device are typically used as storage for files

- Processes use files as a logical storage unit

- Applications dont think about disks, they think about files and request operations to be performed on files

- kernel file system (FS; POSIX API)

- where and how to find and access file

- OS specifies the interface for the file system

- this is to support using multiple different file systems

- generic block layer

- os standardized block interface

- serves as standard for smoothing interactions between kernel and block devices by passing instructions to and interpreting errors from the driver layer

- device driver for each device

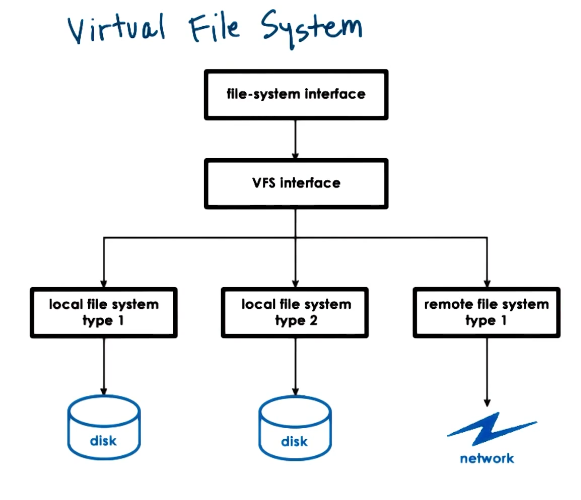

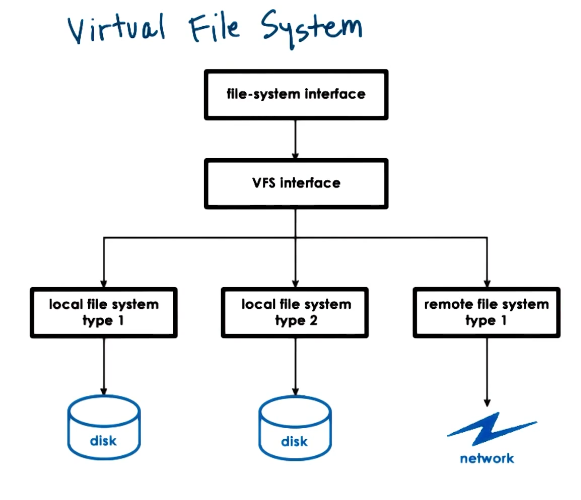

Virtual File System

- What if files are on more than one device

- What if devices work better with different FS implementations?

- What if files are not on a local device?

- To deal with these issues, OS’s use a virtual file system layer

- Hide from applications all details regarding underlying FS

VFS Abstractions

- File == elements on which the VFS operates

- file descriptor == OS representation of file

- used for open/read/write/sendfile/lock/close etc.

- inode == persistent representation of file “index”

- list of all data blocks that correspond to the file

- device, permissions, size, etc

- a directory is really just a file, except its contents include information about files/inodes within

- dentry == directory entry, corresponds to single path component

- /users/ada => /, /users, /users/ada

- if we’re trying to reach a file in ada, need to traverse path. VFS will create dentry element for each path component

- dentry cache will house all directories that have been visited to keep overhead down over time

- soft state, no on-disk representation

- superblock

- superblock == filesystem-specific information regarding the FS layout on storage device

- FS maintains some additional metadata here that helps during operations. What is stored differs among FS implementations

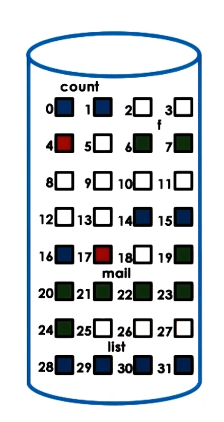

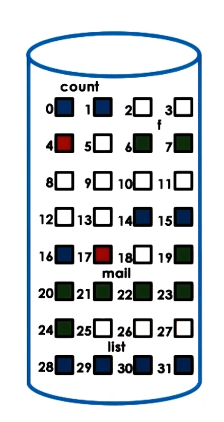

VFS On Disk

- VFS dentries are maintained in soft state by OS, but other components are kept on-disk

- file => data blocks on disk

- inode => track files’ blocks

- also resides on disk in some block

- example: blue and green blocks are each separate files, red nodes are inodes for those files

- Superblock => overall map of disk blocks

- inode blocks

- data blocks

- free blocks

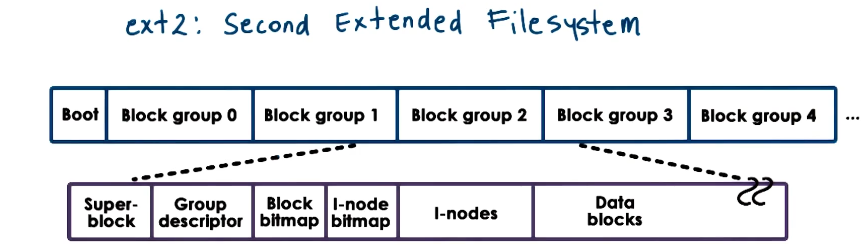

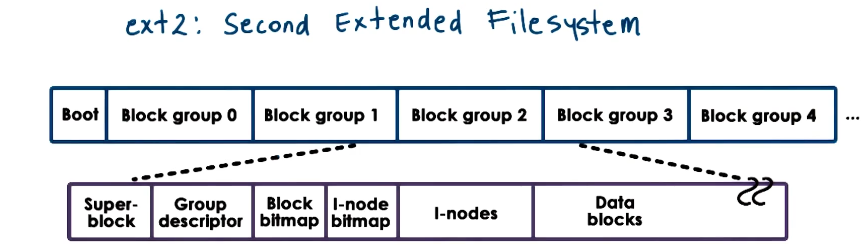

ext2: Second Extended Filesystem

- Was a default FS in several versions of Linux. Most recently replaced by ext4

- For each block group

- superblock => number of inodes, number of disk blocks, start of free blocks

- group descriptor => bitmaps, number of free nodes, number of directories

- bitmaps => tracks free blocks and inodes

- inodes => 1 to max number, 1 per file

- owner, accounting info, how to locate actual data blocks

- data blocks => file data

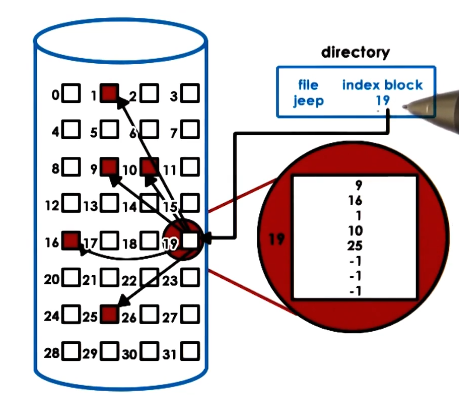

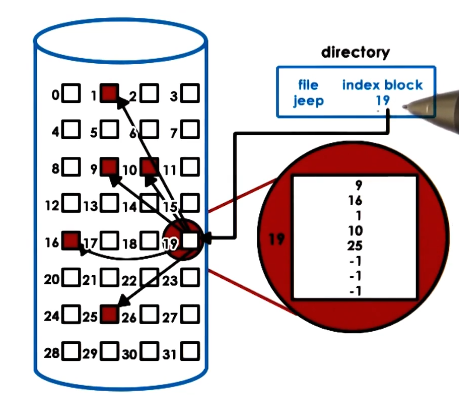

inodes

- are an index of all disk blocks corresponding to a file

- file => uniquely identified by its inode

- inode => list of all blocks and other metadata. uniquely numbered.

- pros

- easy to perform sequential or random accesses to a given file

- cons

- places a limit on file size - number of blocks that can be indexed into an inode

- e.g. 128B inode, 4B block ptr

- 32 addressible blocks x 1kb per block => 32kb max file size

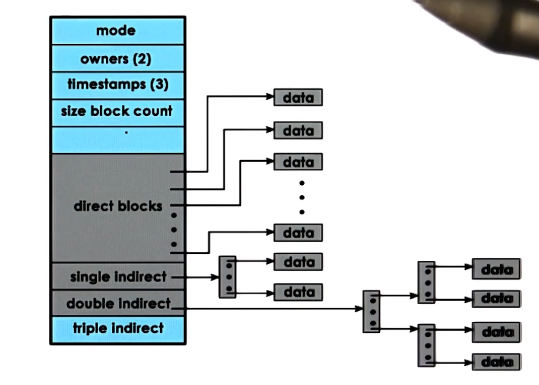

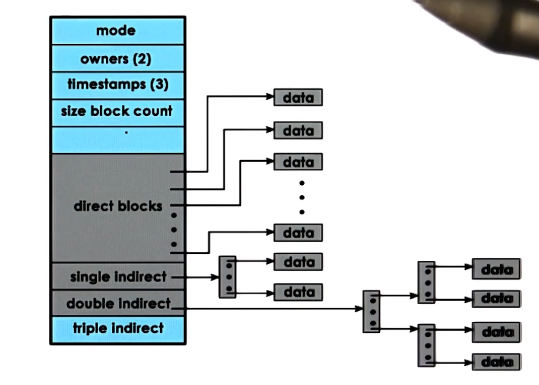

inodes with indirect pointers

- are an index of all disk blocks corresponding to a file

- inodes contain

- metadata

- pointers to blocks of data

- the ones discussed above are known as direct pointers

- indirect pointers solve the space problem

- points to a block full of pointers

- in the above example with 128B inode with a 4b pointer and 1kb block size, this allows a pointer with a single level of indirection to point to 256kb of file data per entry

- double indirect pointers are the same concept with two layers of direction, and blows it up to 64mb per entry

- can layer as many levels of indirection as you want, obviously

- pros

- small inode => large file size

- cons

- file access slowdown as you must access the disk at each step of traversing the indirection

Disk Access Optimizations

- A key goal is to reduce file access overheads

- Caching/buffering => reduce disk accesses

- buffer cache in main memory

- read/write from cache

- periodically flush cache to disk - fsync()

- I/O scheduling => reduce disk head movement

- maximize sequential access (as opposed to random acess)

- e.g writes to blocks 25 then 17 would be reorderd to go 17->25 to reduce disk head movement overall

- Prefetching => increases cache hits

- leverages locality of data on disk

- e.g. if you’re given an instruction to read block 17, also read/cache blocks 18 and 19 because they’re likely to be needed too

- This does add some overhead by adding additional read volume and cache size that may not be needed, but on balance is usually a net win

- Journaling/Logging => reduce random access

- “describe” write in a log: block, offset, value, etc

- periodically apply updates to proper disk locations

- this provides safety and stability to the reorder process, as it allows any reordered but not yet performed disk writes to be kept track of