GIOS Lecture Notes - Part 3 Lesson 6 - Virtualization

Virtualization

What is Virtualization?

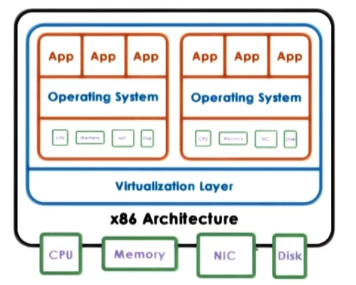

- Originated at IBM in the 60s to support multi-user server environments

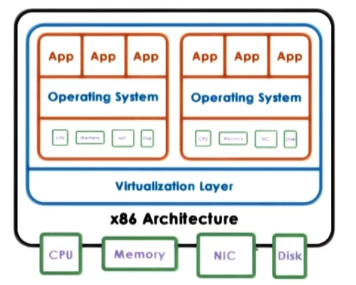

- Virtualization allows concurrent execution of multiple OSs (and their applications) on the same physical machine

- Virtual resources == each OS thinks it “owns” hardware resources

- Virtual machine (VM) == OS + applications + virtual resources (aka guest domain)

- Virtualization layer == management of physical hardware (virtual machine monitor, aka hypervisor)

- Definition (from Popek and Goldberf) == A virtual machine is an efficient, isolated duplicate of the real machine

- Supported by a virtual machine monitor (VMM)

- provides environment essentially identical with the orignal machine. aka “fidelity”

- programs show at worst only minor decrease in speed. aka “performance”

- VMM is in complete control of system resources. aka “safety and isolation”

- doesn’t mean VMM has to inspect every sinle hardware access. Instead it means vmm must determine if/when a given VM is to be allowed hardware access

Benefits of Virtualization

- Pros

- consolidation – ability to run multiple VMs, with their various OS’s and applications, on a single physical platform

- decreases cost, improves manageability

- migration – from one physical machine to another. or even to clone

- availability, reliability

- security

- isolation makes it easy to contain bugs or malware to just one VM

- debugging

- lets researchers quickly introuce features to test

- support for legacy OS environments

- no longer necessary to designate hardware resources to legacy apps or OSs to run a single use case. e.g. “only runs on python2/IE/etc”

Virtualization Models

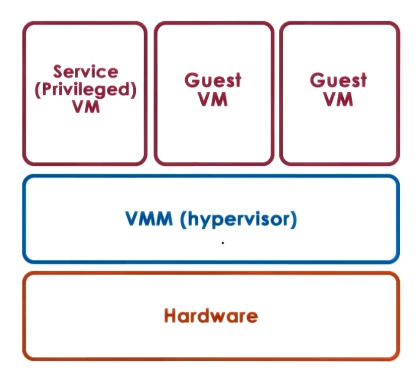

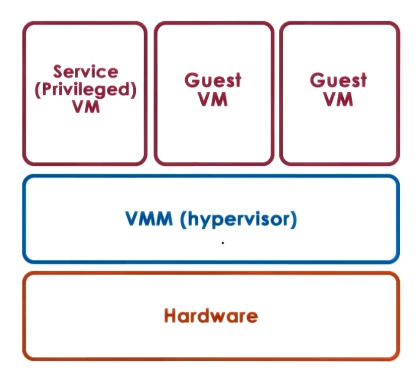

- aka hypervisor-based (type 1)

- VMM (hypervisor) manages all hardware resources and supports execution of VMs

- One issue with this model is devices

- according to the model, VMM must manage all devices

- however, this would require manafacturers to provide driver support not just for all OSs but also for all hypervisors

- to eliminate this, hypervisor includes service (privileged VM) that has full hardware access. This VM deals with devices (and other configuration and management tasks)

- Used by

- Xen (open source or Citrix Sen Server)

- VMs referred to as domains

- privileged VM is referred to as dom0

- guest VMs are referred to as domU’s

- drivers all in dom 0

- ESX (VMware)

- first to market, still has lots of market share

- many open APIs

- to support community developers and users

- drivers in VMM – provided by manufacturers due to market share

- less painful because VMware targets server markets where there are fewer devices in general

- used to use Linux-based control core for configuration tasks, now uses remote APIs instead

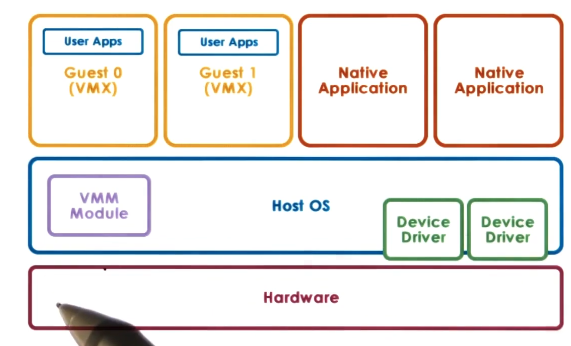

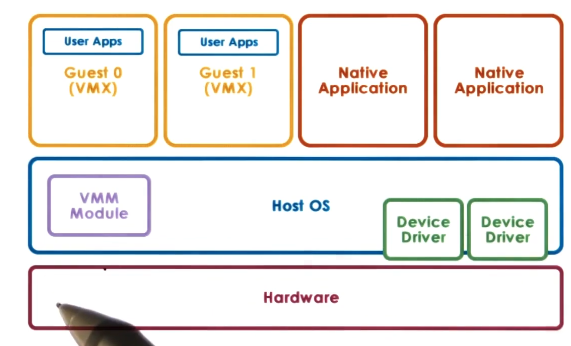

Hosted

- aka type 2

- Host OS owns all hardware

- Special VMM module provides hardware interfaces to VMs and deals with VM context switching

- One benefit of this model is that it can leverage all the services and mechanisms already developed for the host OS

- Can also run native applications on host OS, alongside the guest VMs

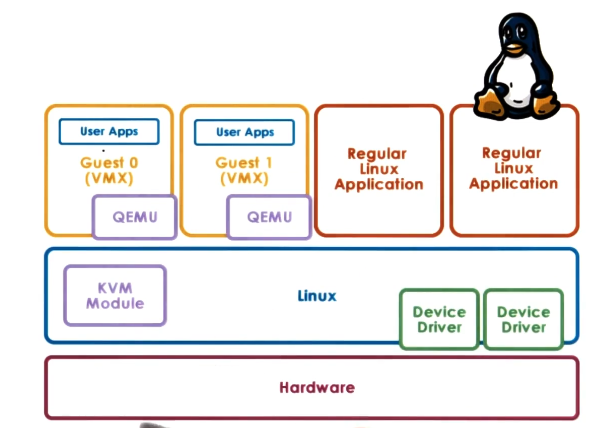

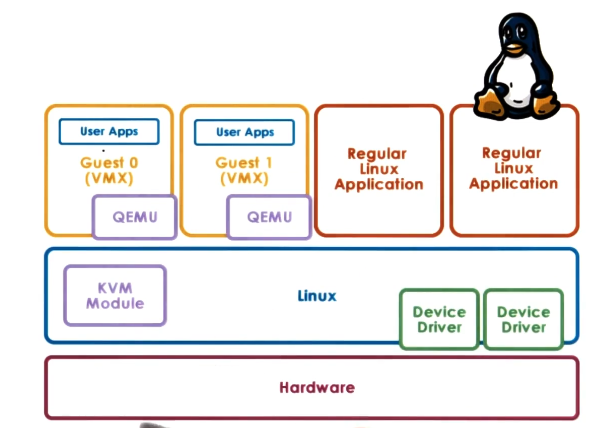

- One example of this model is KVM

- kernel-based VM

- based on linux

- KVM kernel module + QEMU for hardware virtualization

- QEMU runs in “virtualizer mode”, which means that the hardware visible to the guest VM is actually identical to the physical hardware, except that the virtualizer will intervene in certain specific critical operations or instructions

- e.g. I/O management because all device drivers are handled by host OS

- leverages Linux open-source community

- KVM model was actually originally developed as a Linux module to allow Linux apps to take advantage of some of the virtualization-related hardware that started appearing in some commodity platforms

Hardware Protection Levels

- Commodity hardware has more than 2 protection levels

- e.g. x86 has 4 protection levels (rings)

- ring 3: lowest privilege (apps)

- ring 0: highest privilege (OS)

- One way this can be altered for virtualization

- Ring 3: Apps

- Ring 1: OS (guest)

- Ring 0: hyperfisor

- More recent x86 implementations also have 2 protection modes (root & non-root)

- non-root: VMs

- root

- privileged ops by apps will trigger VMexit traps out to the root hypervisor, which will execute as needed and then pass back with a VMentry instruction

Processor Virtualization

- Guest instructions

- executed directly by the hardware

- VMM does not interfere with every single instruction executed by the guest OS and its apps

- so long as the guest processes operate within the resources allocated to them by the VMM

- for non-priviliged operations: hardware speeds => efficiency

- for privileged operations: trap to hypervisor

- hypervisor determines what needs to be done:

- if illegal op: terminate VM…

- if legal op: emulate the behavior the guest OS was expecting from the hardware

- guest should just see that hardware did whatever it expected, doesn’t need to know about hypervisor intervention

x86 Virtualization in the Past

- Problems with trap and emulate

- worked fine on mainframes, but in the 90s on x86 it fell apart

- x86 pre 2005

- 4 rings, no root/non-root modes yet

- hypervisor in ring 0, guest OS in ring 1

- BUT

- 17 privileged instructions that must be run from ring 0, but wouldn’t trap, just fail silently

- e.g. interrupt enable/disable bit in privileged register

- POPF/PUSHF instructions that access it from ring 1 fail silently

- Hypervisor doesn’t know, so it doesn’t try to change settings

- OS doesn’t know, so assumes change was successful

Binary Translation

- One approach to fix the 17 problem instructions was to re-write the binary of the guest VM to never issue those 17 instructions

- this is called binary translation

- commercialized as VMware

- very successful, both commercially and with industry acclaim

- Binary translation:

- goal: full virtualization == guest OS not modified

- no special drivers or policies needed to run

- approach: dynamic binary translation

- instruction sequences about to be executed are dynamically captured from the VM binary.

- done at low-level granularity

- must be done dynamically because often instruction parameters will be input-dependent and so only available at runtime

- inspect code blocks to be executed

- see if any of the 17 problem instructions are to be executed

- if needed, translate to alternate instruction sequence

- e.g. to emulate desired behavior, possibly even avoiding a trap

- otherwise, run at hardware speeds

- some optimizations are available to help speed this up and reduce overhead

- cache translated blocks to amortize translation costs

- distinguish which portions of the guest OS binary should be analyzed, only analyze relevant portions

Paravirtualization

- goal: performance

- give up on unmodified guests

- approach: paravirtualization == modify guest so that:

- it knows it’s running virtualized

- it makes explicit calls to the hypervisor (hypercalls)

- hypercall (behave similarly to system calls)

- package context info

- specify desired hypercall

- trap to VMM

- pass control back to guest after hypercall completes

- Originally adopted and popularized by the Xen hypervisor

- open source hypervisor

- XenSource is a closed Citrix implementation. may have diverged substantially at this point.

Memory Virtualization

- Full virtualization

- all guests expect contiguous physical memory starting at 0

- virtual vs physical vs machine addresses and page frame numbers distinction is also same as native

- still leverages hardware MMU, TLB, etc. for address translation process

- Option 1

- guest page table: VA => PA

- hypervisor: PA => MA

- two page tables, one maintained by guest OS and another maintained by hypervisor.

- Two sets of address translation every time. Too expensive!

- Option 2

- guest page tables: VA=>PA

- hypervisor shadow page table: VA=>MA

- only hypervisor page table is actually used for address translation

- hypervisor maintains consistence between two page tables

- e.g. invalidate on context switch, write-protect guest PT to track new mappings, etc.

- Paravirtualization

- OS knows its executing in a virtualized environment

- so, there is no longer a strict requirement on contiguous physical memory starting at 0

- guest OS explicitly registers page tables with hypervisor

- guest OS still wont have write permissions to the page tables, though.

- every update to page table will cause a trap and pass control to the hypervisor. lots of overhead

- can “batch” page table updates to reduce VM exits

- other optimizations too

- Virtualization overheads, for both full virtualization and paravirtualization, have been substantially reduced or even eliminated on newer platforms

- Details will be discussed in later section

Device Virtualization

- For CPUs and memory

- less diversity to handle for.

- largely due to ISA-level ‘standardization’ of interface

- For devices

- high diversity

- lack of standard specification of device interface and behavior

- 3 key models for device virtualization

- these models were designed before virtualization-friendly hardware changes became common

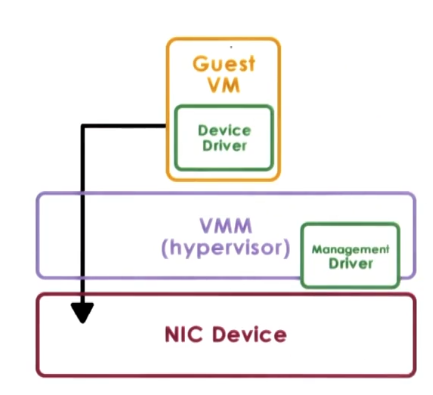

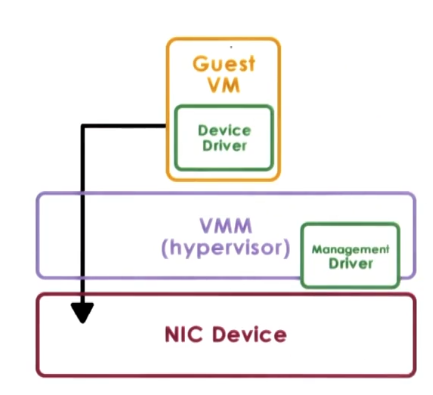

- Passthrough Model

- Approach: VMM-level driver configures device access permissions

- Pros

- VM provided with exclusive access to the device

- VM can directly access the device (VMM-bypass)

- Cons

- Device sharing is difficult

- must continuously reassign which particular VM has bypass access

- VMM must have exact type of device that the VM expects

- not so bad for servers, but not really practical for consumer hardware

- VM migration is difficult

- particularly if there is device-specific state, or even state residing on the device itself, that would not be migrated with the VM

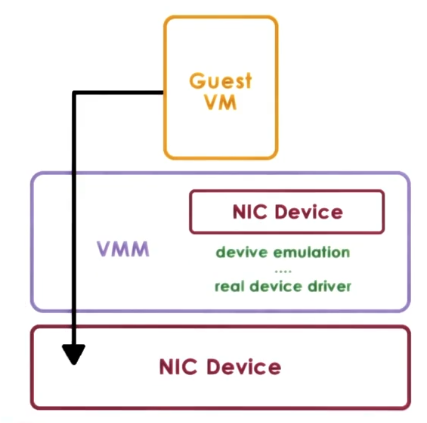

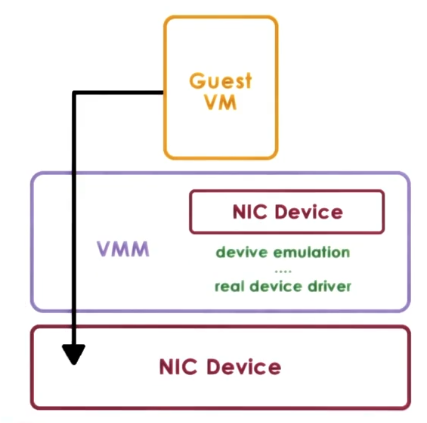

- Hypervisor-Direct Model

- Approach: VMM intercepts all device accesses

- emulate device operation:

- translate to generic I/O op

- traverse VMM-resident I/O stack

- invoke VMM-resident driver

- Pros

- VM decoupled from physical device

- sharing, migration, dealing with device specifics are all simpler and housed in VMM

- Cons

- latency of device operations due to emulation steps

- device driver ecosystem complexities still exist, we just moved them to the hypervisor

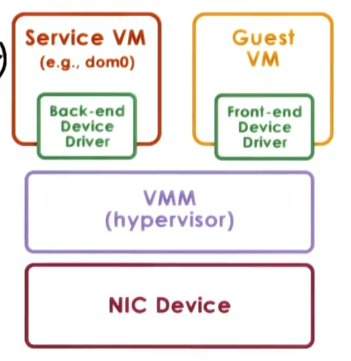

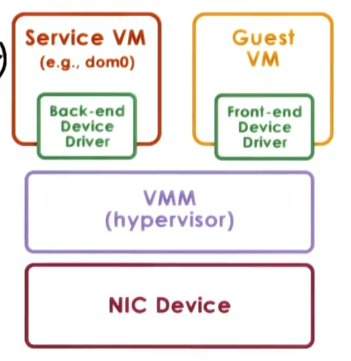

- Split Device Driver Model

- Approach: device access control split between

- front-end driver in guest VM (device API)

- back-end driver in service VM (or host if there is no service VM, as in type 2 virtualization)

- this should really just be the regular device driver that the host OS would use in a non-virtualized scenario

- modified guest drivers for front-end

- has to take application inputs to device and combine/transform them into inputs that the back-end driver can consume

- this means it is limited to paravirtualized guests

- basically serve as wrappers for the device API

- Pros

- eliminate emulation overheads from hypervisor-direct model

- allow for better management of shared services

- the back-end service VM can coordinate shared usage of the physical hardware requested from the front-end drivers

- Cons

- as mentioned above, paravirtualized environments only

- as mentioned above, modified guest drivers required

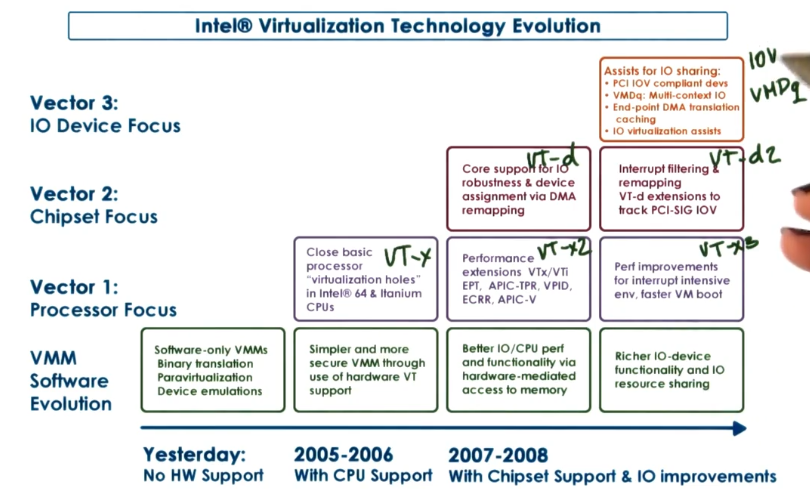

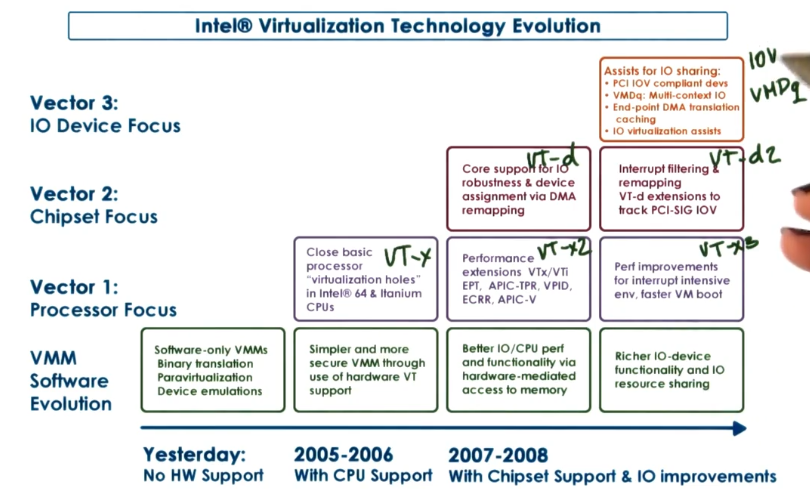

Hardware Virtualization

- Given all the above, and the smashing success of software virtualization both commercially and with industry acknowledgement, hardware companies responded. Specifically by changing their hardware architectures in ways that made them better suited to virtualization

- AMD Pacifica & Intel Vanderpool Technology (~2005)

- close holes in x86 ISA (17 instructions now trap properly)

- modes: root/non-root (or “host” and “guest” mode)

- VM Control Structure

- per VCPU (aka VM Control Block) – ‘walked’ by hardware

- allows hardware processor to understand and interpret information about the state of the virtual processors

- allows hypervisor to know whether a specific system call should trap into root mode or not

- Extended page tables and tagged TLB with VM IDs

- for context switch between VMs (aka world switch) we no longer have to TLB flush entries belonging to previous VM. This is because MMU will match both VA and VM ID when doing translations from VA to PA.

- Multiqueue devices and interrupt routing

- device has multiple logical interfaces where each one can be used by a separate VM

- when device has to deliver an interrupt to a specific VM, it interrupts the core where the VM is executing and not other CPUs

- Security and management support

- allows cleaner and easier isolation

- allows more efficient execution of management ops

- Also additional instructions to exercise the above features

x86 VT Revolution

- Intel’s roadmap for multi-pronged effort on improving VT-friendly hardware. Annotated with “generation names” for each technology.